Writing for the Piano: An Introduction

- Paul Sánchez

- Jul 12, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2024

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Writing for the piano offers almost limitless possibilities for the composer. In this introductory overview, after some brief general suggestions, we will discuss some common pianistic techniques; aspects of the piano, itself; pedaling and sound production; the piano as imitator; score indications; register; and extended techniques and performance considerations. Throughout, I will provide musical examples with video links for purposes of illustration, and will end with a short repertoire list representative of various piano textures.

SOME GENERAL INTRODUCTORY SUGGESTIONS

Have a musical reason for writing what you are writing. Virtuosity for the sake of virtuosity will not win you admirers or performers.

In expert hands, the piano is capable of a wide range of sounds (we’ll discuss this more later), via variations in attack quality, release quality, dynamics, voicing, and use of pedals. Explore a score while listening to recordings of different pianists playing the same work to experience what variety of sounds are possible on the instrument in the same musical context.

Don’t just go with the easiest-to-conceive-of solution. Simply transcribing your improvised accompaniment pattern, for example, will most likely not yield a terribly interesting or beautiful solution (although of course there will be exceptions). Push yourself to discover more detailed, or intricate, or simple, or more elegant, or more angular, et cetera, solutions! The piano is capable of monophonic textures, polyphonic textures, and homophonic textures. Don’t simply default to the most natural option for you, and don’t default to writing all root-position harmonies.

An octave span is safe. Ninths and tenths are possible, but not for everyone!

SECTION 1: SOME COMMON PIANISTIC TECHNIQUES AND THEIR DIFFICULTY

In this section, we'll be exploring the following common pianistic techniques:

For each technique, you'll find a musical example followed by a link to a specific timestamp in a video recording with the same musical example.

It is impossible to put a reliable “difficulty rating” on execution of techniques that may be called for in piano playing. However, the following 5-point scale will at least give a general idea of how difficult a given technique, at a fast tempo, tends to be for pianists to execute:

1 - easy, a beginner could pull this off

2 - students with a few years’ experience could handle this

3 - pianists approaching a professional level could convincingly perform this

4 - professional pianists will play this well

5 - this level of difficulty takes near-superhuman skill to execute, and not all professional pianists will want to deal with it unless there is very good reason

Section 1.1.1. Major, minor, and chromatic scales. Difficulty rating: 1–5

Classically-trained pianists study major and minor scales, so these patterns will be familiar to them. The difficulty of a given passage will be dependent on context and tempo.

Examples:

Franz Liszt: Ballade No. 2 in B minor, S. 171

Section 1.1.2. Non-standard scalar patterns. Difficulty rating: 4–5

Non-standard scalar patterns will most likely be unfamiliar and will need to be learned "from scratch."

Example:

David M. Gordon: "II. The Coal-Bog Giantesses," from Fabular Arcana

Section 1.2.1. Major and minor arpeggiation. Difficulty rating: 1–5.

As with major, minor, and chromatic scales, major and minor arpeggios (along with dominant and diminished arpeggios) will be familiar patterns for classically-trained pianists. Here, too, difficulty will be dependent on context and tempo.

Examples:

Franz Liszt: Ballade No. 2 in B minor, S. 171

Serge Rachmaninov: Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36 (1931)

Section 1.2.2. Non-standard arpeggiation. Difficulty rating: 3–5.

Non-standard (not major, minor, dominant, or diminished) arpeggios will most likely be unfamiliar to pianists, and will need to be learned "from scratch." Be sure that any pattern you create is actually playable (can be reached with the hand).

Example:

David M. Gordon: "III. Concerning the Great Bøyg's Various Reconstructions of Solveig's Song from the Degraded Memories of Melevolent Woodland Spirits," from Fabular Arcana

Section 1.3.1. Blocked chords. Difficulty rating: 1–5.

While blocked chords at a slow tempo are generally not technically challenging, at a fast tempo they can be nearly impossible to perform. The following example from David M. Gordon's Fabular Arcana is extremely difficult.

Example:

David M. Gordon: "IV. Insecta ex Machina," from Fabular Arcana.

Section 1.3.2. Broken chords. Difficulty rating: 1–5.

Broken chords, like blocked chords, vary in difficulty based on tempo and familiarity of shapes (major and minor chords will be most familiar).

Examples:

Graham Lynch: The Couperin Sketchbooks

David M. Gordon: "IV. Insecta ex Machina," from Fabular Arcana

Section 1.4.1. Broken octaves. Difficulty rating: 3–4.

Broken octaves in stepwise motion are effective, sonically, and tend to be less taxing for the pianist than regular octaves.

Example:

Franz Liszt: Ballade No. 2 in B minor, S. 171

Section 1.4.2. Octaves and double octaves. Difficulty rating: 3–5.

Octaves at a fast tempo are difficult, and become more difficult not only with increased tempo but also with increased duration. Short bursts of octaves or double octaves (like the brief moment in the Gershwin example below) are much less taxing than extended passages (like in the example from Liszt's "Funerailles," below).

Examples:

George Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue

Franz Liszt: "Funerailles," from Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses

Franz Liszt: Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata

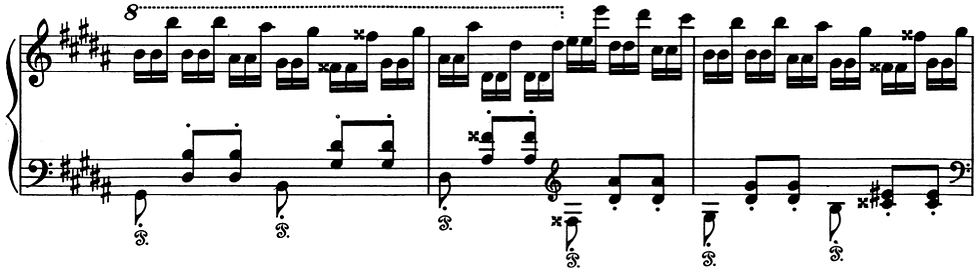

Section 1.4.3. Alternating or interlocking octaves. Difficulty rating: 4–5.

Alternating or interlocking octaves are exciting for the listener, and can often be fun for the pianist. Difficulty depends on speed and on the pattern: the chromatic pattern in the Liszt example below is written beautifully, and falls nicely into the hands, but if Liszt had started the pattern (beginning with the low B-flat on beat 4 of the first measure) in the right hand instead of the left, it would have been much more difficult.

Example:

Franz Liszt: Ballade No. 2 in B minor, S. 171

Section 1.5.1. Repeated notes in one hand. Difficulty rating: 4–5.

Repeated notes in one hand are notoriously difficult. If you write something like this, understand that it is extremely difficult for the pianist, and that if the pianist attempts to play this on a piano that is not in truly exceptional and excellent condition, it will not be possible.

Examples:

Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in D minor, K. 141

Franz Liszt: La Campanella

Section 1.5.2. Repeated notes alternating between hands. Difficulty rating: 3.

Repeated notes achieved by alternating between hands are much easier than repeated notes in one hand. However, if a piano is not in excellent condition, the repetitions will not be possible at a fast tempo.

Example:

Isaac Albeniz: "Leyenda," from Suite Española, Op. 47

Section 1.5.3. Repeated notes within another texture. Difficulty rating: 4–5.

Repeated notes may be possible within another texture, but understand that you are asking for something extremely difficult, and that the piano must be in excellent condition for this to be possible.

Example:

David M. Gordon: "III. Concerning the Great Bøyg's Various Reconstructions of Solveig's Song from the Degraded Memories of Melevolent Woodland Spirits," from Fabular Arcana

Section 1.5.4. Doubled repeated notes. Difficulty rating: 4–5.

Doubled repeated notes are possible, but are extremely taxing (fatiguing) and are only possible on pianos in excellent concert-shape. Be sure that any such passage is brief!

Example:

Graham Lynch: "Glow," from White Book 3

Section 1.5.5. Repeated chords. Difficulty rating: 1–5.

Repeated chords may not be too terribly difficult, and can be an effective sonority-building and texture-filling device. However, these textures can be extraordinarily difficult, as in the opening of Ravel's "Ondine." If a chord doesn’t fit comfortably in your hand (always check!), it most likely won’t be comfortable for a pianist, either; if that’s the case, don’t use it!

Examples:

Franz Liszt: "Funerailles," from Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses

Maurice Ravel: "Ondine," from Gaspard de la nuit.

Section 1.6.1. Hand crossing. Difficulty rating: 4–5.

Hand crossing can be very exciting for the listener, both visually and aurally, and can create some wonderful effects that would not otherwise be possible.

Examples:

Padre Antonio Soler: Fandango

Isaac Albéniz: "El Corpus Cristi en Sevilla," from Iberia, Cuaderno 1

Graham Lynch: "The Rhine," from White Book 3

Section 1.7.1. Double thirds and sixths. Difficulty rating: 4–5.

Double thirds and double sixths are notoriously difficult!

Examples:

Frédéric Chopin: Etude in G-sharp minor, Op. 25, No. 6

Frédéric Chopin: Etude in D-flat major, Op. 25, No. 8

SECTION 2: PEDALING

Most grand pianos have three pedals: damper (right), sostenuto (middle), and una corda (left).

Damper Pedal

The damper pedal (right pedal) raises all dampers on the piano, allowing notes to sustain for as long as the pedal is left down or as long as the strings continue to vibrate.

The damper pedal affects “color.” When the pedal is depressed, it allows strings to sympathetically vibrate with whatever other notes are actually being played, creating a warmer color and richer sound. It may be tempting to imagine that if the damper pedal is depressed, articulation ceases to affect sound, but this is not true. For example, notes played with a light, "carbonated" staccato while the pedal is down will have a very different color than the same pitches played with a tenuto articulation. For a good example of articulation written in a passage designed to be played with the pedal down, see the example from Debussy's "Prelude VI ... Des pas sur la neige, from Préludes, Premier livre" in Section 3, below.

Advanced pianists are able to control gradations of pedal use for special effects.

Sostenuto Pedal

The sostenuto, or middle pedal, causes the damper of any depressed key to remain raised until the pedal is released. It is often used to sustain bass notes under a moving line that requires frequent changing of the damper pedal: in this case, if damper pedal alone were used, it would be much more difficult to sufficiently “clean” moving pitches while maintaining the sound of the desired bass note (although this not always impossible). It may also be used to allow certain un- struck strings to sympathetically vibrate with struck strings.

Una Corda Pedal

The una corda pedal moves the entire action of the piano so that each hammer is only contacting two strings (on three-stringed pitches) or one string (on two-stringed pitches). The resulting effect should be softer than the un-pedaled sound. Just as importantly, the “color” of the sound should be affected. The amount of una corda pedal used makes a difference: one can shift it over just enough that hammers just barely contact the third (or second) string, but don’t entirely miss it; on pianos with string cuts worn into the felt, the una corda’s sound will change depending on where the hammer’s felt contacts the string(s) (on the more plush felt or in the grooves), which can be controlled by the pianists left foot.

SECTION 3: SOUND PRODUCTION ("COLOR")

Professional pianists are capable of producing a wide range of sounds on the piano. For professionals, this sound production (“color”) is a huge part of considerations in performing a work. This sound production, or color, is the sound that leaves the instrument as a result of multiple events occurring in combination at the instrument. Your notation will affect the intentions of the pianist in regards to this sound-production.

Differences in sound production are related to the following factors (among others):

1. Attack, release speed, and articulation: the way in which the pianist initiates sound will have a massive impact on sound production, and the way that the pianist releases pitches affects the overall color and feel of a given texture.

2. Use of pedals: the combination of pedals used and the way that they are used affect color.

• No pedal, one pedal, any two pedals in combination, three pedals

• Timing of damper-pedal initiation (before, concurrently, or after sounding a note or several notes)

• Speed of damper-pedal initiation

• Amount of damper-pedal

• Duration of damper-pedal depression and speed of pedal release

• Amount of una corda pedal used

• Use of sostenuto pedal for pitches that should remain sustained, or for pitches that should be allowed to vibrate sympathetically

3. Voicing. Voicing refers to how a pianist chooses to bring certain voices (pitches) within a teture into the foreground. Take a look at this example from Isaac Albéniz' "El Albaicín," from Iberia, Cuaderno 3. Notice that the right hand in the first two measures is playing an octave filled in by a third: the pianist could, in theory, choose to voice any of the three voices (pitches) above the other two. Furthermore, the pianist could choose to voice one of the remaining two voices over the other. The left hand is simultaneously playing a B-flat pedal tone and another moving voice. The pianist will need to decide how to voice the left hand, choosing to voice either the moving line or the pedal tone. Finally, the pianist will need to decide how the three voices in the right hand relate to the two in the left hand in terms of voicing. There are almost limitless possibilites in the combinations of voicing that are possible and the relative levels of each voice in relationship to the others.

In the example from Graham Lynch's "Absolute Inwardness," the homophonic texture in the first three measures varies from 5–6 pitches. In the recorded example, the top voice is brought to the fore. The voicing continues in the fourth measure (measure 93), and I allowed the high notes on the second eighth note of each beat to sound as echoes.

4. Dynamics: the dynamic level of any sound produced will affect its color, and a range of colors are possible within any given dynamic level.

It is important to remember that any texture or figuration that you write is not a specific sound. Rather, anything you write is merely an approximation of your imagined ideal; it is a suggestion, one that may be shaped in a potentially-infinite variety of interpretations by different musicians depending on their abilities, mannerisms, and sensitivities, and on musical context. However, your notation, and any annotations or other indications you make, will affect the way a given passage will be understood by pianists, and hence should make it more likely that their interpretation is more like what you were imagining.

In summary, it is important to consider color possibilities for two reasons: 1) color is an issue - realize that multiple “colors” could result from the same notes on a page; 2) give pianists sufficient clues to guide them towards a sound production that is, hopefully, in line with what you want!

Following are examples of musical moments rife with color possibilities. I would recommend listening to various recordings of each example performed by different pianists, and notice how the color of each varies from the last. Notice also how notation and indications may affect color.

W. A. Mozart: Sonata in F major, K. 332, ii. Adagio

Claude Debussy: Prelude VI ... Des pas sur la neige, from Préludes, Premier livre (notice the portato articulation in the right hand E and A-flat octaves in the third measure of the example, and that this articulation is meant to be performed with the damper pedal down: articulation affects color even with the damper pedal depressed!)

Frederic Chopin: Nocturne in C minor, Op. 48, No. 1 (notice the mezza voce indication)

Claude Debussy: Prelude III ... La puerta del vino, from Préludes, Deuxième livre (notice the indications âpre ("harsh") and avec de brusques oppositions d'extrême violence et de passionnée douceur ("with brusque contrasts of extreme violence and passionate tenderness"). For a detailed discussion of this piece and other Spanish-inflected works, see my article The Poetics of Deep Song: Albéniz, Debussy, and Lorca.

Claude Debussy: Prelude X ... La cathédrale engloutie, from Préludes, Premier livre

SECTION 4: THE PIANO AS IMITATOR

Much may be learned from how composers have used the piano to imitate other instruments. Studying pieces written explicitly to imitate other instruments, or pieces that are transcriptions of works for other instruments, can provide useful exemplars of ways to create certain sound effects and colors.

Following are some works in which the piano may imitate other instruments, or which are transcriptions of works for other instruments.

Alessandro Marcello/J.S. Bach: Concerto in D minor, BWV 974. In this work, you'll hear Bach's transcription of the sounds of string orchestra and solo oboe.

Joaquín Rodrigo: Aranjuez, Ma Pensée (1968). This is Rodrigo's own piano transcription of the "Adagio" from his Concierto de Aranjuez, for solo guitar and orchestra.

Claude Debussy: Prelude IX ... La sérénade interrompue, from Préludes, Premier livre (notice the indication quasi guitarra). In this work, guitar, voice, and other instruments are imitated. For a detailed discussion of this piece and other Spanish-inflected works, see my article The Poetics of Deep Song: Albéniz, Debussy, and Lorca.

David M. Gordon/Paul Sánchez: Fader, stilla våra andar. This is my transcription of David M. Gordon's song for soprano and piano. Of particular interest apart from the vocal color of the voice line is the rhythmic complexity, in which the pianist sometimes has to play 5 against 4 against 3.

Chopin's Nocturnes and Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words have excellent examples of cantabile writing for the piano.

SECTION 5: INDICATIONS AND OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Dynamics

Dynamics (traditionally) are not absolute, but are relative to one another. Dynamics carry connotations: piano “cantabile” may be very similar in actual decibel level to mezzo forte, but a pianist would likely interpret the same passage differently given these two dynamic indications.

Articulation

As previously discussed, articulation is important to indicate, even if the pedal will be in use!

Left and Right Hand

These are indications that may be used to identify right or left hand, respectively: m.d., m.g.

Pedaling

Pedaling is a very complex issue, as evidenced by our previous discussion on the subject. The decision to attempt to indicate pedal, then, should be carefully considered.

Think first of the demographic you are writing for. If you are writing for children, or for beginners or students, it is probably worthwhile and helpful to indicate pedaling.

If you are writing for advanced pianists, it may not be possible, or at least not practical, to attempt to indicate pedaling with any sufficient degree of detail.

In this case, here are two possibilities:1) Indicate that pedal may be used (e.g. “with pedal”), but don’t attempt specifics; 2) Indicate specific pedaling only for special effects (for example, a series of pitches completely blurred together in one pedal (Beethoven Tempest).

Your other score indications, including slurs and other articulation markings, should give the pianist enough information to intelligently and successfully use the pedal. If you would like the pedal to “override” your articulation markings, you may want to indicate that.

Multiple Staves

Multiple staves may be used in order to make voice-leading or layering more clear to the pianist.

Examples:

Isaac Albéniz: Corpus Cristi en Sevilla

Serge Rachmaninov: Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2

Graham Lynch: "The Hesperides," from White Book 3

David M. Gordon/Paul Sánchez: Fader, stilla våra andar.

SECTION 6: MELODY, REGISTER, AND CHORD VOICING

The register in which you place a melody will greatly affect its effect. Look at the Chopin Nocturnes for wonderful examples of melodic writing for the modern piano (his piano was very similar to ours, much more so than Mozart’s piano or Beethoven’s piano). The range he tends to use is approximately from middle C to the C two octaves above that (rather like soprano range). Melody may also be placed much lower (Franz Liszt's "Funerailles") or higher (Arvo Pärt's "Fur Alina"), but most commonly for special effects. When you are writing melodies, be aware of whether you are writing a line that behaves like a singer’s melody, or if you are writing a polyphonic melody (like Bach uses in the cello suites, for example). Either is fine, but they will create vastly different effects and, of course, are used for different purposes.

Voicing of chords has a tremendous influence on the effect produced. If you are going to use block chords, look for examples in the classical literature for some ideas of voicing, and listen to good jazz pianists, whose voicing is always well-considered and intentional. Close voicing tends to sound cluttered and not very appealing. Generally, left-hand voicings (unless in a higher register), sound “prettiest” with spacing of a seventh or octave.

SECTION 7: EXTENDED TECHNIQUES

Extended techniques for the piano allow composers to create sounds on the instrument well outside the realm of natural piano timbre. Be aware, however, that use of extended techniques will very likely make a composition more difficult to program, and that venues may not be willing to allow extended techniques to be used on their instruments. I would only recommend using extended techniques that do not pose any risk of damaging a piano, which will make it much more likely that venues will allow your work to be performed.

If you come across an effect you like, but which could be damaging to an instrument, try to find a safe alternative. For example, instead of using fingertips to mute a string, which can cause damage to piano strings via skin oil, I've used a squeegee in my compositions Gothic Atonement and NEFERTARI. Following is an example from "Ghosts," the second song of Gothic Atonement.

A tiny (incomplete) sampling of other extended techniques follows:

Prepared piano (vinyl screws and paper on strings): David M. Gordon: Mysteria Incarnationis

Plectrum: David M. Gordon: Mysteria Incarnationis

Harmonics: George Crumb: A Little Suite for Christmas, A.D. 1979

Other string techniques: Henry Cowell: The Banshee

Retuned piano: David M. Gordon: Fabular Arcana

One pianist on two microtonally-tuned pianos: David M. Gordon: Consolation New

SECTION 8: A SAMPLING OF INTERESTING PIANO TEXTURES

In this section, I'll provide a short list of pieces that feature some interesting textures that may serve as inspiration for composers.

Frederic Chopin: Etude in A-flat major, Op. 25, No. 1 (melody over a rippling texture)

Frederic Chopin: Etude in C-sharp minor, Op. 25, No. 7 (melody in bass, plus imitation)

Frederic Chopin: Etude in C minor, Op. 25, No. 12 (melody in tenor, echoed in soprano)

Franz Liszt: Ballade No. 2 in B minor (melody in tenor register)

Franz Liszt: "Un Sospiro," from Three Concert Etudes (melody over/in moving texture)

Serge Rachmaninov: Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36, 2nd movement

(melody in the middle of a huge texture)

SECTION 9: CONCLUSION

I hope that this introductory overview of considerations for writing for piano has been helpful! We have barely scratched the surface, here, so please comment below or write me directly with any questions or requests for a more in-depth look at any particular topics. The best way to learn is to study other composers' work and then try your hand at bringing to life the sounds you imagine: happy composing!

Comments